James Vibert

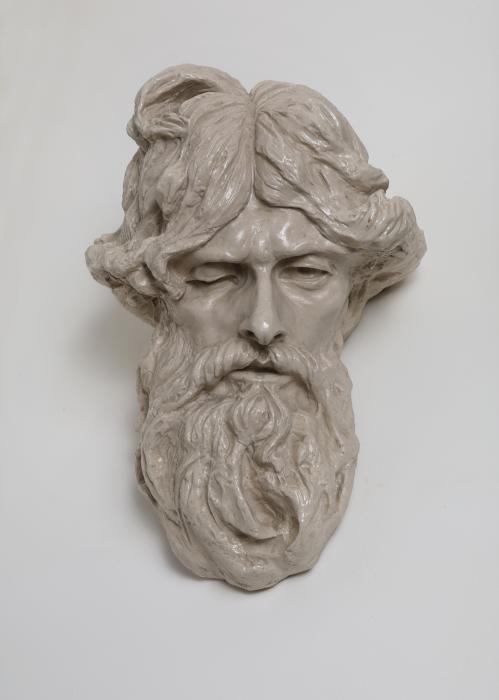

With the ceramicist Émile Muller / Portrait of Marcel Lenoir or Head of John the Baptist 1894-1898

At the bottom of the hair:

-signed (handwritten): J. VIBERT / E Muller

-numbered (stamp): 4B

H. 33, W. 24.5, D. 22.5 cm

Provenance

- France, private collection

Bibliographie / Émile Muller

- 1896 CATALOGUE : Émile Muller et Cie, Catalogue de l’Exécution en Grès d’un Choix d’Œuvres des Maîtres de la Sculpture Contemporaine, Paris, Georges Petit, 1896.

- 1898 COLLETTE : A. COLLETTE, « Les grès artistiques », in Le Moniteur du dessin, de l'architecture et des beaux-arts, n°2, mai 1898, p. 20-22.

- 2009 CATALOGUE : Michèle RAULT, Catherine MERCADIER (sous la dir. de), La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry, le beau et l’utile, catalogue d’exposition, Choisy-le-Roi, parc Maurice Thorez, 12 juin – 20 septembre 2009, Ivry-sur-Seine, Périgraphic, 2009.

Bibliographie / James Vibert

- 1898 IBELS : André IBELS, James Vibert sculpteur, Paris Bibliothèque d’art de La Critique, 1898, p. 18-19.

- 1919 MOROY : Élie MOROY, « James Vibert et la statuaire symboliste », Le Mercure de France, 1er novembre 1919.

- 1942 FONTANES : Jean DE FONTANES, La vie et l'œuvre de James Vibert, Statuaire suisse, Genève, P.-F. Perret-Gentil, 1942.

- 2012 CATALOGUE : Sculptures 1880-1910, catalogue d’exposition, Paris, Galerie Mathieu Néouze, 2012.

- 2020 CHEVILLOT : Catherine CHEVILLOT, « James Vibert et Rodin », in. Guerdat, Pamela, Pèlerin sans frontières : mélanges en l'honneur de Pascal Griener, Droz, 2020.

Bibliographie / Marcel-Lenoir

- 1994 CATALOGUE : Marcel-Lenoir 1872-1931, catalogue d’exposition, Montauban, musée Ingres, 30 juin – 2 octobre 1994, repr. p.3.

Exhibition

- 1900, Paris Universal International Exposition (Swiss—Group II—class 10, #35)[1]

Other proof in public collection

- United States, Portland Art Museum, Inv 2002.8

JAMES VIBERT, symbolism and stoneware

James Vibert, a Swiss sculptor, was born in Carouge in 1872 and died in Plan-les-Ouates in 1942. He studied in Geneva at the École des Arts Industriels and in Lyon with a skilled metalworker. He spent the years from 1892 to 1903 in Paris, where he discovered the salon of the Rose-Croix (the Rosicrucians) and became friends with other Swiss artists, such as Ferdinand Hodler[2] and Rodo (Auguste de Niederhausern), which brought him into contact with Parisian symbolist circles; he shared a number of their interests, including dreams, dark visions, and breaking down the barriers between the arts. Vibert did a portrait of one of the movement’s central figures, Puvis de Chavannes, on an enameled stoneware medal in 1895.

In 1894, Vibert spent several months in Rodin’s studio[3], and like Rodin, who collaborated with the Manufacture de Sèvres, and created stoneware pieces, first with Edmond Lachenal in 1895 and then with Paul Jeanneney, a student of Carriès, in 1904, he explored the expressive possibilities of ceramics.[4] Technical progress in the field of enameled stoneware dovetailed with a growing interest in the decorative arts, inciting a number of sculptors to begin working in this material. In 1891, the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts opened a section for the decorative arts, and the Art Nouveau movement, spearheaded by Siegfried Bing and his gallery, which opened in 1895, created new opportunities for the medium. Its extensive decorative possibilities were also greatly enhanced by the colorful nuances of enamel. Many sculptors, following Art Nouveau architects, collaborated with editors in ceramics. Some, such as Antoine Bourdelle, worked with Alexandre Bigot, while others, such as James Vibert, turned toward Émile Muller.[5] Though in fact, Vibert worked with Émile Muller’s son, Louis d’Émile Muller, who took over from his father in 1889.

ÉMILE MULLER, ceramicist

Charles-Eugène Muller was born on September 21, 1823, in Altkirch, a small municipality in the Haut-Rhin in Alsace. At the beginning of the 1850s, he built a large workers’ housing project in Mulhouse, and in 1854, he started a tile-making business under the name Émile Muller & Cie, with headquarters in Mulhouse. Around the same time, he acquired a large piece of land, more than 10,000 m2 at Ivry-sur-Seine.[6] The business grew rapidly and was soon “a colossal enterprise that makes everything, or almost everything that comprises, in its infinite variety, industrial ceramics.”[7] Émile Muller created the décor for the Palace of the Fine Arts and Liberal Arts at the 1889 universal exposition. That project constituted the apogee his career’s development and was seen as his finest achievement, crowning his success in France and abroad. Émile Muller died on November 11, 1889, shortly after the exposition closed. The business was passed down to his only son, Louis d’Émile Muller, who took it in new directions.

Louis-Émile Muller, known as Louis d’Émile Muller, was born on October 26, 1855 in Mulhouse. An artist himself, it was under his direction that Émile Muller & Cie had its artistic flowering. He began reproducing masterpieces of sculpture in stoneware at the Ivry workshops, beginning by adding reproductions of the works of old masters, such as Jean Goujon, Clodion, Luca della Robbia, Donatello, and Verrocchio, to his catalogues, as well as large- reproductions of antique works.

Louis d’Émile Muller later added contemporary statuary to his catalogue, dealing with artists directly for the exclusive right to reproduce models of their works. According to the Catalogue de l’exécution en grès d’un choix d’œuvres des maîtres de la sculpture contemporaine (Catalogue of the Creation in Stoneware of a Selection of Works by Masters of Contemporary Sculpture), published by Muller’s company in 1896, he made editions of models by Alfred Boucher (1850-1934), Jean Dampt (1854-1945), Alexandre Falguière (1831-1900), Jean-Antoine Injalbert (1845-1933), Jeanne Itasse (1865-1941), and Jean-Désiré Ringel d’Illzach (1847-1916), among others. The catalogue cites four works by James Vibert.[8] In 1897, there were “more than 300 models” that were “currently available” through Émile Muller & Cie.[9]The year 1897 marks a turning point in the history of Émile Muller & Cie’s editions of art stoneware; that year, they opened an office at 3 rue Halévy in Paris’ 9th arrondissement. The office also served as a permanent showroom for the stoneware editions produced at the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry, and thus also functioned as a salesroom. In 1908, with the gradual loss of interest in the Art Nouveau movement and increasing financial burdens, Émile Muller & Cie went bankrupt.

Vibert’s Stoneware

Though he also made works in bronze, plaster, terra-cotta, and pewter, James Vibert was equally interested in his works in stoneware. He made various decorative objects, such as inkwells, pitchers, and vases, and, as with Alexandre Charpentier, these objects offered occasions for sculptural detail (see, for example, a vase titled L’Ivresse (Intoxication), held in the Metropolitan Museum of New York inv. 2004.119). In 1900, he showed a collection of his stoneware pieces at the Universal Exposition; the Portrait of Marcel Lenoir was among the works presented in a showcase, where it was titled Head of John the Baptist.[10] As is usual when a sculptor collaborates with a ceramicist, the work is signed by both the sculptor and the ceramicist: J. VIBERT / E Muller. There is also a number “4B” stamped on the work, though it is not known what this refers to.[11]

Figures of Bearded Men, Figures of Saint John the Baptist

Vibert’s sculptures include a number of bearded heads. Though this one clearly bears the features of his friend the symbolist painter Marcel-Lenoir, the sculpture described here has also been titled Head of Saint John the Baptist, notably when it is placed on a circular platter, as is the copy held in the Portland Art Museum.[12] As far as is currently known, this copy on the platter is the only other copy of the model.[13]

In our opinion, the Portrait presented here would not necessarily be considered a Saint John the Baptist because it was conceived to be hung and presented vertically (it has a flattened cut-out on the back that suggests that it was removed from the platter, and two holes have been pierced to allow it to be hung). It is a portrait of Marcel-Lenoir that echoes symbolist ideas and the symbolist vision: “One searches in vain for the deep expression of the artist, and yet all of his features have been faithfully sculpted. (…) Though it is Marcel Lenoir, it’s also an interpretation of a degenerated Christ (…)” explained his contemporary, the poet André Ibels.[14]

This emaciated face of a young man, whose features surge up from a dynamic background, is framed by abundant hair and a bushy beard, with one eyelid almost closed, and the other opened onto a haggard eye, the mouth slightly agape. It evokes the abandon of ultimate suffering. There is an unmistakable drama about it …

There are other, similar, suffering physiognomies among James Vibert’s works. Vita in Morte (Life in Death), which was also presented at the 1900 Universal Exposition, is another suffering bearded man. This model, like many of the artist’s works, was a figure for a monumental project representing the cycle of human existence initially titled Altar to Nature and then later, The Human Effort:[15] “like Rodin’s Gates of Hell, his Human Effort appears throughout Vibert’s career.”[16]There is another study for Human Effort that is also the buste d’homme barbu (bust of a bearded man); it’s held in the collections of the museum in Carouge, Switzerland, and its features also seem to be those of Marcel-Lenoir, in a very Rodin-esque style. And finally, there’s a bust that has disappeared, titled Les Visions (1894);[17] it also had the same “à la Marcel-Lenoir” physiognomy and was very close to the Tête de Saint Jean-Baptiste[18] by Ringel d’Illzach,”[19] another symbolist artist who frequented the same circles as Vibert and had models edited by Émile Muller.

MARCEL-LENOIR, Mystical Figure

Marcel-Lenoir, born Jules Oury in 1872 in Montauban, was a painter, designer, engraver, illuminator, and jeweler. He was close to the community of the Rose+Croix (the Rosicrucians) around Sâr Péladan until 1902. He and James Vibert moved in the same circles. “An eccentric character walking around Montparnasse with his Christ silhouette in a kind of artistic cabaret,”[20] he regularly posed for other artists. Always dressed in black, wearing a large hat and wooden shoes, he cultivated an air that was “slightly frightening: tall, with his thin face, narrow, piercing eyes, and thick hair, sometimes long, sometimes short, but always with a straight part in the middle.”[21] In 1897, Marcel-Lenoir showed his project for a Christ Pardoning the World at the Salon of the Rose+Croix. In that piece, he used a self-portrait for Christ’s face, and he stated, “I believe that suffering is necessary for work.”[22] A photograph by Dornac shows Marcel Lenoir in his studio in Paris around 1898 with his portrait by Vibert on his worktable, but it is a slightly different version, the one held in the museum of Carouge [23].

[1] See the general official catalogue, Paris. Exposition Internationale Universelle, Documentation of the musée d’Orsay (James Vibert box).

[2] Ferdinand Hodler painted a portrait of James Vibert, which is now in the Art Institute of Chicago: 1907, oil on canvas, 64.7 x 66 cm Inv1926.212.

[3] Vibert’s time in Rodin’s studio is not well documented. It seems that he was not an assistant; he may have been an intern, supported by a Lissignol grant. Furthermore, according to certain sources, he entered Rodin’s studio in 1891, while according to others, it was closer to 1892 or even 1894 (see 2020 ARTICLE, p. 242). It is generally agreed that he spent 18 months in the studio, and that he spent time with François Pompon there.

[4] Anne Lajoix, “Auguste Rodin et les arts du feu” (“Auguste Rodin and the Arts of Fire”) Revue de l’Art, vol. 116, no 1, 1997, p. 76 (DOI 10.3406/rvart.1997.348330, lire en ligne [archive], consulted March 3, 2020).

[5] “With the exception of a few works done by Massier or Dalpayrat, it seems that, in fact, most of the ceramic objects conceived by Vibert were edited by the Muller company.” CATALOGUE Mathieu Néouze, 2012, #35.

[6] The Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry-Port opened at 6 rue Nationale in Ivry-sur-Seine around 1854.

[7] 1897 RAMBAUD: Yveling RAMBAUD, “L’Exposition de la céramique. La Maison Émile Muller,” in Le Journal, July 31, 1897, p. 2.

[8] 1896 CATALOGUE, p. 15: link to the catalogue

[9] 1897 RMBAUD, p. 2.

[10] Catalogue general official, Paris. International Universal Exposition, Documentation of the musée d’Orsay (James Vibert box).

[11] This type of numbering, followed by the letter B can be seen on other stoneware pieces edited by Muller. But after making a study of its different uses, we know that it is not an edition number and, a priori, also not a reference to the enamel nor to a mold …

[12] James Vibert, The Head of Saint John the Baptist, ceramic, Accession Number: 2002.8.

[13] Two sales at public sales are worth mentioning, though it is not known if it was this copy each time or other copies: November 23, 2015 (Yves Plantin Collection—Galerie de Luxembourg), Art Auction France, lot 632, and November 26, 1976, Art Nouveau, Art Deco Sale, Drouot, lot 82 (Documentation of the musée d’Orsay, James Vibert box.)

[14] 1898 IBELS, p. 19.

[15] It seems that the final project was never realized.

[16] 1942 FONTANES, p. 82

[17] Reproduced by a drawing on an issue of the journal La Plume, May 1, 1896, #169 (Documentation of the musée d’Orsay, James Vibert box).

[18] Jean Désiré Ringel d’Illzach, Head of Saint John the Baptist Standing on a Plate, 1884, terracotta, H. 44 cm, musée d’Orsay, inv. RF4289.

[19] 2020 ARTICLE, p. 246.

[21] 1994 CATALOGUE, p. 12.

[22] Raison ou Déraison du peintre Marcel-Lenoir (Reason or Unreason of the Painter Marcel-Lenoir), volume I, Paris, L’Abbaye, 1908, p.43.

[23] 1994 CATALOGUE, p. 3.