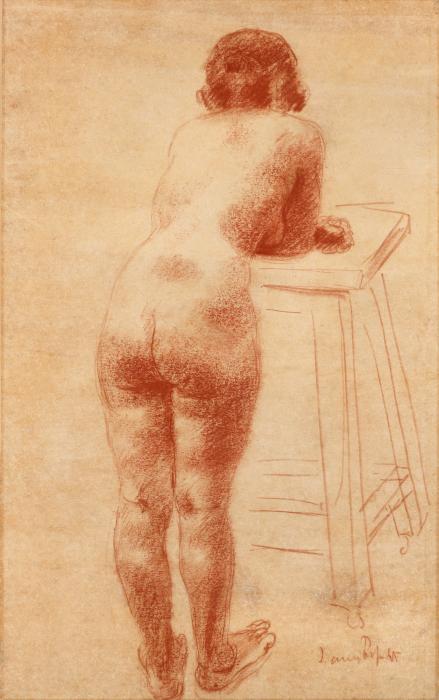

Jane Poupelet

Female Nude from the Back

Red pencil

Signed : Jane Poupelet

H. 59 ; W. 36 cm

Provenance

- France, Private Collection

Bibliography

- 1930 KUNSTLER: Kunstler, Charles, Jane Poupelet, Paris, Éditions G. Crès et Cie, 1930.

- 2003 DUMAINE: Dumaine, Sylvie, Les dessins de la statuaire Jane Poupelet (1874-1932), collection de dessins déposée à Roubaix, La Piscine, musée d’art et d’Industrie-André Diligent (The Drawings and Statuary of Jane Poupelet (1874-1932) drawing collection held at Roubaix, La Piscine), master's thesis, written under the direction of Frédéric Chappey, Université de Lille III, 2 volumes, 2003.

- 2005 CATALOGUE: Roubaix, La Piscine-musée d’Art et d’Industrie André Diligent, Jane Poupelet 1874-1932 « la beauté dans la simplicité » ("Beauty in Simplicity"), Éditions Gallimard, 2005.

"Since Renoir, no one has been able to render, as she does, the sensual charm of a woman, the sweetness of radiant skin, the solidity of muscles in action, the ease of muscles once relaxed; no one has ever been able to suggest, as she has, with just a few strokes of her pen or a few dashes of ink, the complexity of a foot or of a knee."[1]

CONTEXT OF THE WORK'S CREATION AND ARTISTIC DEVELOPMENT

Jane Poupelet began drawing as a child. In 1882 at the age of 8, she was sent to Bordeaux to live with an "old spinster"[2] who instructed her in the art of drawing for more than ten years. Her efforts were rewarded in 1892 when she obtained a "certificate of ability" to teach drawing in schools. The same year, she enrolled in the local school for fine and decorative arts. In addition to being the first woman admitted to that school, she was also, with five other women, the first to be allowed to take courses in anatomy and to be present at dissections at the medical school in Bordeaux. In 1895, her studies gained her the governmental diploma of Professor of drawing. With this second diploma in her pocket, Poupelet, still quite young, went to Paris; she arrived sometime between the end of 1896 and the beginning of 1897. There, she drew the city's monuments and attractions, filling up many sketchbooks. Yet what would capture her interest the most at the beginning of the 20th century, in addition to animals, was the female form.

JANE POUPELET'S FEMALE NUDES

The sanguine drawing presented here is of a female model seen from behind. Standing, angled forward with her arms crossed, the young woman is leaning on a sculpture stand placed before her. Jane Poupelet was not interested in representing ideal beauty as conceived by the ancients. She wanted to show a truth: "Art consists in presenting both beauty and ugliness. That's its whole purpose … beauty in art is the splendor of the truth. Beauty is not truth; it is not a single thing; it varies according to the individual."[3] And so, in this case, she drew a woman in a natural pose, seeking neither to highlight nor to obscure her curves and volumes. Furthermore, as she's seen from the back, the model has become anonymous, making this not a drawing of a particular woman, but of all women.

Above all, Poupelet was interested in the ephemeral quality of motion. Sylvie Dumaine, who studied Jane Poupelet's drawings, has described how she would "let the model move around and then would mentally interrupt her when the motion interested her. In this way, the woman offered herself to the artist's gaze without knowing it, and the artist could, effectively, break into her intimacy."[4]

JANE POUPELET'S DRAWING

Jane Poupelet captured this arrested motion with the aid of an accessory, the sculpture stand. Though it's barely sketched in, it allowed her to record the depth of the space through lines of perspective. The body of the young woman occupies the entire vertical space of the drawing; her left foot touches the bottom edge, while her head is close to the upper edge. This tight framing creates a forceful presence, which is further emphad by the highly structured composition. In the center of the sheet, the lines of the body echo those of the sculpture stand: her legs, straight and taut, are almost parallel to those of the stand, while two diagonal parallels are formed by the feet of both the model and the stand, on the one hand, and, on the other, by the torso, which is leaning over and resting on the top of the stand, which draws the viewer's eye into the background.

There are various striking contrasts that make this drawing particularly lively; for instance, some parts are lightly sketched in while others are more highly worked. In addition to the sculpture stand, the model's feet and hand have remained just lightly sketched. It's also clear that anatomical reference points were added to the back of the knees, which the artist decided to leave in. "As in her sculpture, Jane Poupelet valued the unfinished."[5]

Another contrasting element is light. A strong chiaroscuro has the model's back drenched in light, while her legs, in shadow, are only highlighted at prominent points, and the inside of the right upper-arm remains in shadow. This contrast points to another, that between the continuous, delicate trace that outlines the figure and the strength of the shading. "While Jane Poupelet remained faithful to contours, she could "attack" the modeling with the savagery of a wild beast with claws. [ …] The cross-hatching is frenetic and harsh, and the modeling is violent and frank."[6]

The tight framing around the body, the density of the sanguine pigment, and the sculptural quality of this drawing are reminiscent of the Bordeaux master of painting and drawing Georges Dorignac (1879-1925). Jane Poupelet corresponded regularly with him between 1916 and 1923. "Some of Poupelet's heavily shadowed and tightly framed drawings of female nudes invite comparisons with those of Dorignac."[7]

This drawing occupies a significant place in the body of Jane Poupelet's artistic work. Though sometimes also used as preparatory studies, all of Poupelet's drawings are, above all, works in their own right, and yet all the elements of statuary art are here. As Patrice Dubois has phrased it: "What is it that characterizes the drawings of a sculptor? The sense of living form expressed through a model in the depth of space. The articulation of volumes is integrated into an architecture whose force is based entirely upon light. It's this synthesis of volume, plane, and light, attained through visible realities, that distinguishes the drawings of sculptors."[8]

[1] 1930 KUNSTLER, p. 10.

[2] 2005 CATALOGUE, p. 13.

[3] 2005 CATALOGUE, p. 83.

[4] Ibid., p. 79.

[5] Ibid., p. 81.

[6] Ibid., p. 82.

[7] Georges Dorignac (1879-1925), le trait sculpté (the Sculpted Line), exhibition catalogue, Roubaix, La Piscine – musée d’art et d’industrie André Diligent, November 19, 2016 – March 5, 2017, Bordeaux, musée des Beaux-Arts, May 18 – September 17, 2017, Gand, Éditions Snoeck, 2016, p. 49.

[8] Dessins de sculpteurs (Sculptors' Drawings), exhibition catalogue, Paris, Galerie Malaquais, November 4 – December 24, 2005, Paris, Leconte Montrouge, p. 6.